Lawsuits take time, sometimes dragging on for years. So when a settlement finally arrives, whether from an individual claim or a class action, it’s easy to assume the process is over.

But it’s not.

Sooner or later, a tax form will show up in your mailbox or inbox. However, receiving a tax form doesn’t automatically mean your settlement is taxable. In the U.S., some settlements are tax-free, others are taxable in full, and many fall somewhere in between.

In this guide, we’ll separate taxable settlements from non-taxable ones and explain how to report settlement payments on your tax return when reporting is required.

Key takeaways

- Settlement taxability depends on what the payment is for, not the lawsuit label

The IRS applies the “origin of the claim” rule. If a settlement compensates for personal physical injury or illness, it is generally tax-free. If it replaces income or punishes wrongdoing, it is usually taxable. - Many settlements are mixed, and each portion must be treated separately

A single settlement can include both tax-free and taxable amounts. Wages, interest, punitive damages, and non-physical emotional distress are typically taxable, while physical injury compensation often isn’t. - Attorney fees and prior deductions are common reporting traps

In many cases, the IRS treats the full settlement as income even if a part went to your lawyer. Reimbursements for medical expenses you previously deducted can also become taxable under the tax benefit rule. - Settlement taxes only matter if you actually receive the settlement

Many people never claim the class action settlements they are eligible for. Settlemate helps solve that by automatically finding settlements you qualify for and helping you file claims easily, so the next settlement you report is one you didn’t miss.

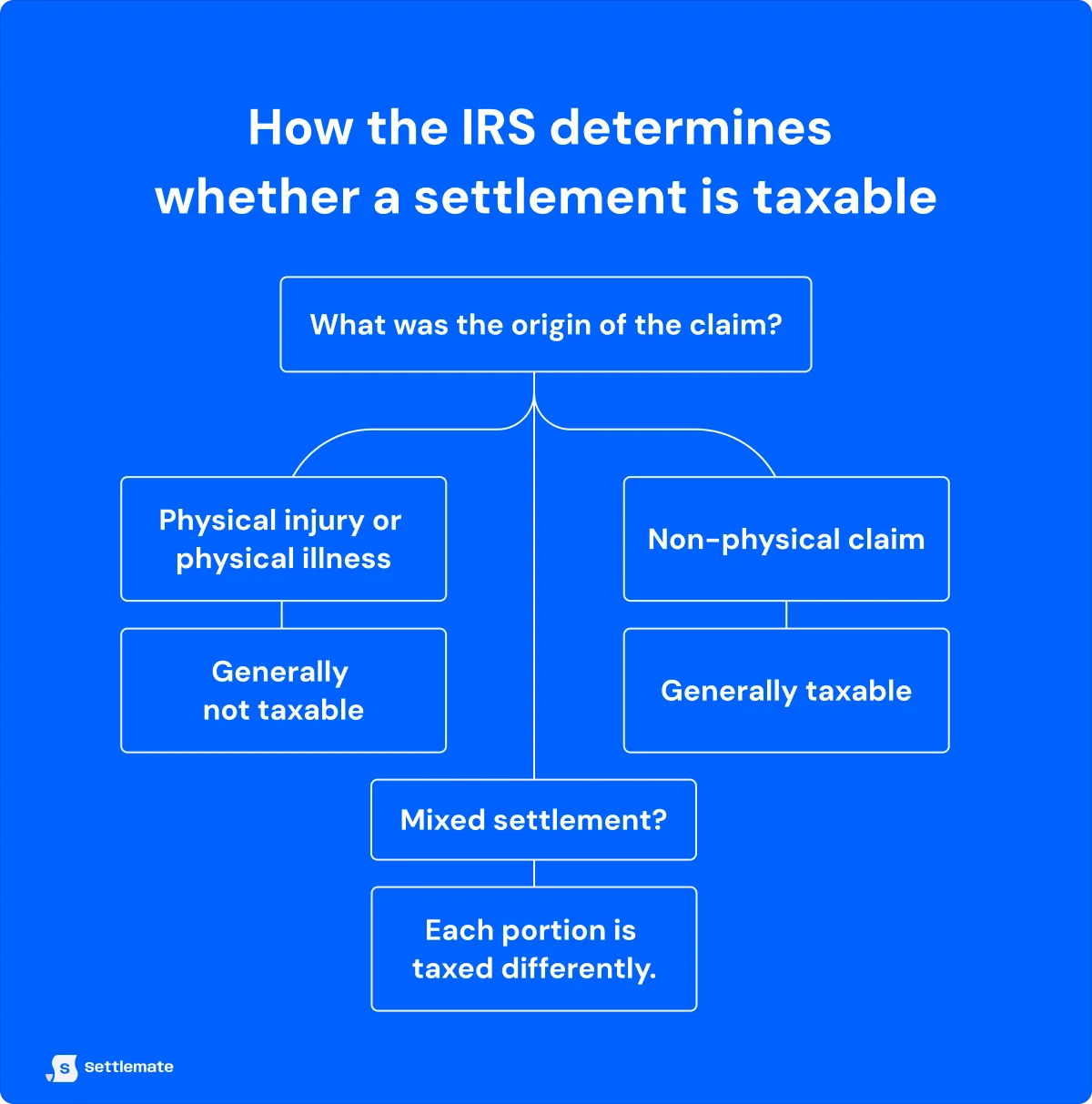

How the IRS decides whether a settlement is taxable

Under Internal Revenue Code Section 61, all income is taxable unless a specific exception applies.

For settlements, the main exception covers payments for personal physical injuries or physical illness, which are generally tax-free.

By contrast, settlements tied to lost wages and emotional distress without physical injury, punitive damages, and other non-physical claims are typically taxable.

To make that call, the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) applies what’s known as the “origin of the claim” rule. If the claim is about replacing income, the settlement is taxed as income. However, when the claim is compensating for a physical injury, it may be excluded from tax.

Note that many settlements include multiple components, some of which are taxable, while others aren’t. That’s why it’s important to understand how each portion is treated before reporting it on your tax return.

Tax-free settlement payments

If your settlement falls into one of the six categories below, you don’t have to report it as taxable income.

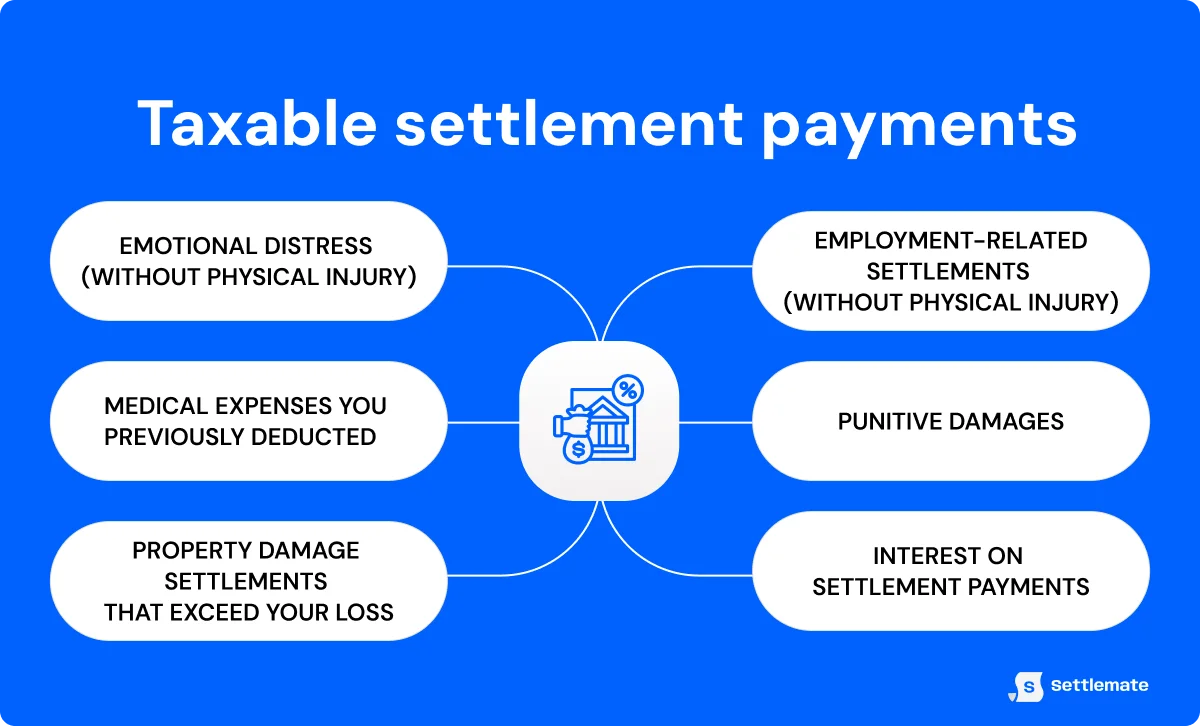

Taxable settlement payments

The following six settlement payment categories are taxable, meaning the IRS expects you to report them as income and pay tax accordingly.

1. Emotional distress (without physical injury)

Settlement payments for emotional distress that isn’t tied to a personal physical injury or physical illness are generally taxable.

That’s because under current tax law, mental anguish on its own doesn’t qualify for an exclusion.

This applies to cases like:

- Workplace harassment

- Discrimination or retaliation

- Wrongful termination

- Defamation or humiliation

Although these damages are taxable, they aren’t treated as wages, which means they aren’t subject to federal payroll taxes.

In addition, you may reduce the taxable amount by medical expenses related to the emotional distress, but only if you didn’t previously deduct those expenses or didn’t receive a tax benefit from the deduction.

2. Medical expenses you previously deducted

Settlement payments that reimburse medical expenses you previously deducted on Schedule A (Form 1040) are taxable under the IRS’s tax benefit rule, which prevents you from receiving a double tax benefit.

If you deducted medical expenses over multiple years, the taxable portion of your settlement is usually calculated on a pro rata basis, based on how much tax benefit you received each year.

3. Property damage settlements that exceed your loss

When it comes to settlements for property that can be repaired at a reasonable cost, non-taxable compensation is typically limited to the repair costs and related consequential expenses.

If the property is destroyed, or if repair costs exceed its value, non-taxable compensation is usually limited to the property’s fair market value immediately before the loss (the price the property would’ve sold for on the open market just before it was damaged).

Any amount paid above these limits is treated as taxable income and must be reported.

4. Employment-related settlements (without physical injury)

Settlement payments tied to employment disputes are generally taxable because they replace income you would’ve earned on the job.

This includes compensation for:

- Back pay and front pay

- Severance or dismissal pay

- Wrongful termination settlements

- Discrimination or harassment claims (such as age, race, gender, religion, or disability)

5. Punitive damages

Punitive damages are almost always taxable. Unlike compensatory damages, they aren’t intended to compensate you for any losses. They’re awarded to punish the defendant and deter similar conduct in the future.

Punitive damages may be awarded in cases involving:

- Intentional harm

- Gross negligence

- Fraud or malice

- Willful or reckless disregard for safety

The only exception is certain wrongful death cases, where a person’s death was caused by another party’s negligence or misconduct, and state law allows only punitive damages to be awarded. In these narrow cases, punitive damages may be excluded from income under Internal Revenue Code Section 104(c).

6. Interest on settlement payments

Interest paid on a settlement is always taxable, even if the underlying settlement itself is tax-free.

This applies to both:

- Pre-judgment interest – Interest that accrues while the case is pending

- Post-judgment interest – Interest that accrues after a judgment until payment is made

From the IRS’s perspective, interest is compensation for the time value of money, not for an injury or loss.

How settlement payments are reported to you

In a settlement, tax forms are issued to you by the parties that make or process the payment. You don’t request these forms, and you don’t get them from the IRS. They’re part of standard third-party reporting.

Depending on how the settlement is paid, tax forms may come from:

- The defendant – Often responsible for reporting settlement payments, especially when taxable components are involved

- An insurance company – Commonly issues forms when it funds settlement payments, particularly for non-physical injury claims

- An employer – Issues forms in employment-related settlements, such as those involving back pay or severance

- A law firm – Typically issues forms for lawyer fees or payments to experts and service providers, and may issue additional forms to reduce reporting risk

These settlement payers might send you tax forms even when some or all of your settlement is ultimately non-taxable. That’s because failing to issue required forms can trigger IRS penalties, so many payers choose to play it safe and report the payment.

The table below outlines the common tax forms used in settlement cases:

How to report settlement payments on your tax return in 5 steps

This step-by-step guide covers the basics, but complex or high-dollar settlements may still be worth running by a tax professional.

Step 1: Review your settlement agreement carefully

Start with the settlement agreement, and identify what each portion of the payment is for.

If the settlement is itemized, use the stated allocations to determine which amounts are taxable.

If it’s a lump-sum payment, you must reasonably allocate the settlement yourself based on the underlying claims. Otherwise, the IRS may treat more of the payment as taxable.

Step 2: Check which tax forms you received

Confirm whether you received a Form W-2 for wage-related settlement payments or a Form 1099-MISC for other settlement income. The form type affects how you report the payment, not whether it’s taxable.

Step 3: Account for lawyer fees properly

Lawyer fees can complicate settlement reporting because, in many cases, the IRS treats the full settlement amount as income, even if a portion was paid directly to your lawyer. That means you may need to report the gross settlement amount, not just the amount you received after legal fees.

In certain cases—most notably employment-related claims and whistleblower actions—the tax code allows an above-the-line deduction for qualifying lawyer fees. This prevents you from being taxed on money you never actually kept.

Step 4: Report taxable settlement income on the correct tax forms

If any portion of your settlement replaces wages, such as back pay, front pay, or severance, you must report that amount on your Form 1040 as wages, using the figures shown on your Form W-2. These payments are treated like regular salary and may already reflect federal, state, and payroll tax withholding.

Other taxable settlement payments that aren’t wages are reported as other income on Schedule 1. If you received a Form 1099-MISC, the amount you report should generally match the taxable portion shown on that form.

If the settlement income is connected to self-employment or business activity, report it on Schedule C. You may be able to deduct related business expenses, but the net amount could be subject to self-employment tax.

For mixed settlements—those with both taxable and non-taxable components—report only the taxable portion as income.

Step 5: Keep supporting documentation with your tax records

You should always save your settlement agreement, tax forms, and any related correspondence.

Keep these records for the IRS-recommended retention period, which is generally at least three years after you file, or longer if the settlement involves large amounts, complex allocations, or amended returns.

If the IRS questions your return, this documentation is what backs up how you reported the settlement.

Settlement taxes only matter if you actually get paid

Understanding how to report settlement payments on your tax return only matters after you’ve actually received a settlement. Most people never get that far.

Many class action settlements require you to file a claim, and plenty of eligible people never do. They don’t hear about the case, miss the deadline, or give up once the paperwork starts. The result is the same: money you’re owed goes unclaimed.

Settlemate fixes that.

This app automatically finds class action settlements you’re eligible for and helps you claim them with minimal effort.

Here’s what Settlemate offers:

- Automatic settlement matching: Settlemate identifies settlements you qualify for without you having to search.

- Pre-filled claims: When possible, claim forms are filled out for you, so you don’t have to involve lawyers.

- Tracking and alerts: You’ll see claim status, payout estimates, and deadlines in one place, with notifications when action is needed.

- Clear proof guidance: If documentation is required, Settlemate tells you exactly what to submit and why.

Download Settlemate from the App Store or Google Play and start finding settlements you’re owed before the paperwork shows up.